My new Chemistry Script, the principal of Induction and other strange thoughts

Hello gamers and developers alike. For those not familiar with the game Byproduct it is a minamalistic automation game which I made for the 2025 GMTK Game Jam with the theme of 'Loop.' Since the Jam I have been extending the game with various features and polish. However the past few weeks I have been working on a singular peice of tech to ease my development of the game.

I thought this piece of tech was quite interesting, so here I am writing a Tech Blog post about it. If your interested in procedural content generation stick around, you may find this interesting.

The Problem:

Byproduct only has factories. There are no conveyor belts, there are no trains, drones or delivery trucks. To get any items from A to B you have to process them through various cyclic recipe chains to the desired location. So the interaction of recipes is central to the entire gameplay experience.

Now I hear you, recipes are central to all automation games. However the structure goes deeper here, without any other item movement mechanic the shapes of working structures in your overall factory are directly tied to the recipes. In fact what appears to matter most is the connection between various items via their recipes. In mathematics this is know as Topology. You may recognise the idea from a subway map. Destinations don't have direct distances displayed on the map, but rather they are displayed with their connectivity as easy to see as possible.

The practical problem I was facing? It was bl**dy annoying to code all those recipes accurately in the godot engine.

There were several times during the jam a recipe wasn't properly input as I forgot to double click a resource. I ended up editing the wrong resources several times and sometimes missing some recipes all together.

Godot has a feature that allows you to code custom resources. Which is perfect for implementing various unique ideas for any individual game. Need to describe a pickup item in game? Make a resource for it. How about an equipable weapon. Another resource, perhaps with a link to the pickup version. So that is what I used for my own game. Three different types of resources; ItemResource, FactoryResource, RecipeResource.

Wouldn't it be nice if Godot could just make all these resources for us?

The Solution:

Lets make Godot make all the resources for us!

I'm using this project as a bit of a learning excercise for using Godot. I tried various things to begin with. I started out with a rather heavyweight solution of creating my own plugin. Needless to say this was a little overboard. After looking around for various tutorials on making plugins for Godot I stumbled across this one about creating EditorScripts without needing to even create a plugin. Perfect for what I wanted to achieve.

EditorScripts are simple scripts that only need to define one function _run(). They can then be invoked by pressing Ctrl+Shift+X or opening up the command palette (Ctrl+Shift+P) and searching for your script. I didn't even know Godot had a command palette!

So what are we going to make our new script do then? Let me get a little phylosophical first.

How will our player interact with these recipes? If I don't wish to simply divulge the full list of recipes the player will need to experiement or make best use of clues we leave for them. How will players reason about this new virtual world they find themselves. They will be looking for patterns, they will be testing edge cases and making mini hypothesies about the structure of recipes within the game. They in a sense become mini scientists testing the world around them. This all hinges on the idea of Induction. We depend on the world around us staying relatively consistent. When it does we build models of those consistencies and question areas that seem to intermingle or contradict. This is science.

We want to lean into that. Recipes should relate to one another. Patterns should stand out in a wider context. And for this game I have singled out three categories of patterns:

- Consistent allegory linked with each factory. A cycler factory loops over a predefined subgroup of items. A sifter seperates and sorts. etc.

- Common sense ideas from the world around us apply within the game. Fire burns, Ice is made of Water, etc.

- Recipes repeat in specific configurations.In other words, the structure of a recipe remains consistent over all relevant inputs.

The first two are ideas I must keep in mind as a designer. But there is little I can do to automate these ideas (yet). They will define what recipes I do attempt to put into which factories however. Later I can make use of a feature I will describe shortly, but the main focus of our automation challenge to start with is the third pattern. Common configurations resulting in the same recipe.

My first thought was to create a whole DSL to describe my recipes. A Domain Specific Language is a mini programming language used to solve a very specific problem. And it's almost always the wrong solution to a programmers problems. Another case of me over engineering my problems.

Tags and Mappings:

So after slapping myself on the wrist I asked myself what is needed to solve this problem. Godot already has a scripting language I can use to describe the recipes I need, gdscript. If I can describe each set of recipes as a function, then I can supply values from an iterator to populate each case I need. This lines up nicely with the idea of consistency. We map a set of already consistent values 1, 2, 3, etc, onto our recipes gaining a backbone of a pattern from them.

The question now becomes, how do we map these values consistently? The most general answer I came up with were tags which map to meta values. Every item we make within the script we can tag with little descriptive strings; 'elemental,' 'primary,' 'hot,' 'fluid,' etc. We can then link a value with each tag.

If we take the first four elemental items as an example; Air, Fire, Earth, Water. One of the tags we attach to these elements is the tag 'primary' for primary elements. But we also link a set of numbers with each. Which goes something like this:

Air, tags: {'elemental': true, 'primary': 1}

Fire, tags: {'elemental': true, 'primary': 2}

Earth, tags: {'elemental': true, 'primary': 3}

Air, tags: {'elemental': true, 'primary': [0, 4]}

You'll note that the last element in the list maps to two values, 0 and 4.This way we can program a proceedure to look for items with specific tags mapped to specific values. And when we search for the item tagged with 'primary, 0' or 'primary, 4' both options produce the item for 'Air.' This does require a little contrivance on my end to implement but it makes the mapping far more descriptive.

Given the above set of tags we may want to implement a cycle as follows (psuedo code):

function make_cycle(index):

make a recipe from 'primary, {index}' to 'primary, {index+1}'

for each index in 0 (inclusive) to 4 (exclusive):

make_cycle(index)

And now we have a cycle which is reminisent of the Aristotelian Elements.

We may ask however, what is the point of specifying these recipes in terms of a mapping. Why not just specify each set of recipes in a loop if all we are going to use is a mapping from some set of consecutive numbers to a set of recipes.

First lets consider a simple example of mapping the days of the week onto some set of recipes. If we consider them in order we are likely to write them as follows:

Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday

But this isn't the only common sense way to order these days. There is also:

Sunday, Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday

And if we are extra cheeky we can order them alphabetically:

Friday, Monday, Saturday, Sunday, Thursday, Tuesday, Wednesday

If the commonality between two different sets of recipes is the days of the week, we have just applied a consistent set of mappings to said recipes. Even further, the first two orders are cyclic and the last is a sequence with a begining and end. If the player is given some sort of clue that indicates the days of the week they have a basis from which to derive these sequences. Especially if the relationship between each day and each recipe was evident some how. But crucially using different ordering mechanics to each of the recipe sets modifies the relations between the sets of recipes. Try imagining lining up the recipes next to their respective days (or their inputs at least), then reordering them based on one of the other orders.

So using this example we have shown how to borrow some sembalance of structure from one kind of sequence. But it doesn't even need to be a sequence:

for each i in 0 to 10:

for each j in 0 to 10:

make_another_recipe(i, j)

The above maps the structure of a square onto a set of recipes. The key is the relation between any two elements in a mapping.

State and Search algorithms:

So now we have an idea how we will produce the data associated with each resource. We now need to carefully consider how we will store and make use of this data. It would be tempting to simply process all the recipes as described above, producing each resource in turn and outputting them to my assets folder. But there is a couple of issues here, or perhaps missed opportunities if we go this route.

First of all, we wont always be making these resources afresh. Sometimes we will be modifying existing resources or at least testing new configurations against them. We will want to construct our desired resources and then compare it to existing the resources within the project. For future reference we'll call a collection of related resources a Chemistry.

Another consideration is potential conflicts and arbitrary choices. If we want to full explore all the possibilities available to us we should search through all the possibilities for the most pleasing version. This requires us to structure our algorithms a little more carefully.

We can store a desired chemistry in a single state object:

class ChemistryState:

items...

factories...

recipes...

tags...

function copy() -> ChemistryState

By defining our collections of recipes, items and factories as part of a state class we can copy it at any point and test a new addition. Checking for collisions in recipes or other properties, like 'is it trivial to reach a certain end game item?' or 'how obscure is the sequence of recipes to reach a desired state?'

In other words this approach allows for a search based approach and backtracking through any potential chemistries. This can be implemented recursivley by copying the state class and sending it into a search pass, or through some more complex graph based setup. Either way by bundling our state together like this we have the option for any approach we desire.

Although I should mention at this point, I have yet to implement any kind of search algorithm. Implementing a simple toy example and then reimplementing the original Elemental Chemistry did not require that much 'machinery.' I'll explain later why I think it was still worth it to include this addition.

Given the above setup our script now does something along the following lines:

- Computes a 'Chemistry' utilising tags and mappings.

- Searches for items that match those in the state class. Stops and reports any clashes or missing resources when found.

- Searches for factories that match those in the state class. Stops and reports any clashes or missing resources when found.

- Searches for recipes that match those in the state class. Stops and reports any clashes or missing resources when found.

- Maps recipes onto factories. Stops and reports any clashing or missing mappings when found.

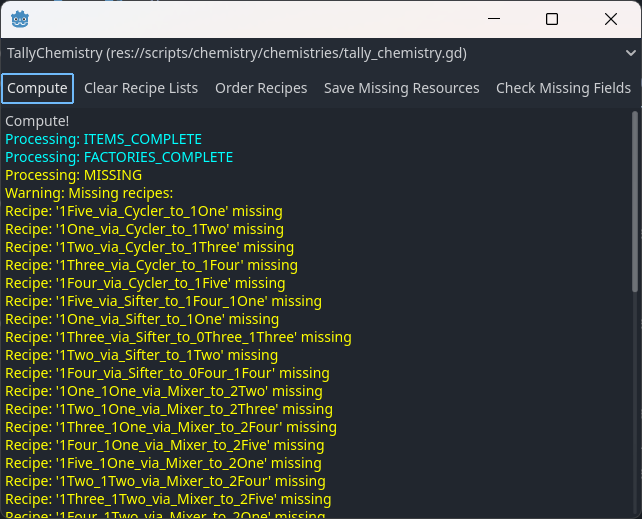

The resulting script window can be seen below:

This is where having a script like this shows it's full utility. As you can see in the above image there are several utility functions built into the script. Ones to clear existing recipe lists, others to order existing recipes in a sensible order. Also, since not all values in these resources can be precomputed, there is a button to scan for obvious missing fields.

When missing resources are spotted the script stops and outputs all the anomalies for me to review. I can stop and read throught to ensure I'm not about to overwrite a bunch of prior work, before pressing the save resources button. Which uses the ResourceSaver inbuilt Godot class to save the given resources into my assets folder.

Proceeding step by step I can implement an entire chemistry incrementally using the code I have written. Rather than fumbling with the individual resources myself.

So next time I require a new chemistry, all I have to do is implement a new subclass to the Chemistry class. The script will then search my project for all the scripts that directly subclass the Chemistry class via the function:

ProjectSettings.get_global_class_list()

Which can then be selected via the options box at the top of the window.

The Final Problem:

There is only one problem with the implementation so far. The implementation of each of the recipes ended up being rather unreadable:

var solver_cycler = FunctionalChemistrySolver.new(func (new_state: ChemistryState, index: int):

var sc = new_state.init_recipe([_ms(_ffift(new_state, 'primary', index), 1)],

[_ms(_ffift(new_state, 'primary', index+1), 1)], FACTORY_CYCLER_NAME)

return evaluate(ChemistrySolver.SolveResult.UNIQUE, sc)

, range(4))

Each 'solver' encapsulates an individual set of recipes. A prepatory step for later search functionality. Essentially we will want to iterate over the range given at the end. This function should initialise the Aristotelian cycle of elements as we described above.

The issue comes with the awkward use of shorthand functions _ms (short for make stack, a stack of items) and _ffift (first filtered item for tag). I know most coders are cringing at this line. My instinct is to make every function as readable as possible, like the init_recipe method. But further line length simply obscured even further what the recipe was meant to represent.

What is the solution? DSL to the rescue!

We dissmissed the use of a DSL earlier as it complicated the issue at hand rather than simplified things. The actual advantage of a good DSL however is to make specific structures easier to read. We changed over to a full gdscript version of the code as we didn't want to code all the intricacies of a full programming language. We can leverage the power of an already existing programming language.

But what if we could have the terse representation of a DSL together with the flexability of a programming language. So why not just make a mini DSL for the structure of a recipe? And leave out the complex calculation portion of the code. Have a look at the following:

p#i -> p#j; cyc

This represents a recipe from one primary element to another using the cycler factory. The hash tags represent a tag mapped to a value, in this case the 'primary' tag mapped to what ever value 'i' takes. But we are still missing the values of 'i' and 'j.' That is where we supply a dictionary of mappings for substitution values. The full line looks like this:

new_state.init_recipe_from_string("p#i -> p#j; cyc", _mappings.merged({"i": index, "j": index + 1}))

Here we are introducing the recipe of the form "p#i -> p#j; cyc" with 'i' substituted with index and 'j' substituted with index + 1. the _mappings value is a dictionary with already existing substitutions. We can build up maps of substitutions by merging them with more and more specific values. For instance _mappings has an entry for the letter 'p' as a simple substitution for the 'primary' tag.

This makes things a lot easier to read and the coding of the mini DSL was only around 50 lines of code. The trick is that we have made the DSL simple to parse with no complex moving parts. There are no internal expressions and every element can be divided up with a simple split operation. Split is a handy string function that splits a string by a given substring. So we start with the large feautres like the semicolon ';' and arrow '->'. Then we move onto the individual ingredients split by spaces. Finally looking for hash tags and other filter like options.

When we reach an identifier (a string of characters defined by alpha numeric symbols) we can then consult the mapping dictionary to see whether we need to substitute a value. All of the heavy lifting of computing values can be done within the gdscript and passed onto the recipe via the mapping.

The end result looks something like this:

var solver_cycler = FunctionalChemistrySolver.new(func (new_state: ChemistryState, index: int):

var sc = new_state.init_recipe_from_string("p#i -> p#j; cyc", _mappings.merged({"i": index, "j": index + 1}))

return evaluate(ChemistrySolver.SolveResult.UNIQUE, sc)

, range(4))

Which I believe looks a lot more readable, if it hadn't been crammed all into a tight space by the itch.io site (looks better in the editor I promise)!

So why all this effort:

This seems like a lot of effort for a simple learning project. But the motivation to write this utility comes down more to my major goals rather than anything short term. My aim is to make games that give the player a sense of discovery. Having everything laid out by the developer cheepens that experience for me. The times I have felt this feeling in games the most sharply is when emergent behaviour creeps out of the wood work to surprise you and even the developers themselves.

So my aim is to make games that deliberatly persue that emergent behaviour.But in persuit of that I don't want to lose the leash and end up with a game that doesn't feel like a game.

There is an area of study called Proceedural Content Generation. It covers more than proceedural terrain generation and proceedural textures, etc. Games like Dwarf Fortress exemplify this approach but also quickly get out of hand. There is a reason the phrase 'losing is fun' is the catchphrase of the Dwarf Fortress community. And don't get me wrong, losing is certainly fun in Dwarf Fortress, I love the game. But that may not be the case in what ever game I make.

I won't suddenly find the holy grail to PCG but this project is my initial attempt to step in that direction. In future games can I make further use of the tech to make immersive/deep crafting systems? Who knows, I'd sure like to find out, and there is only one way to do that.

Still just a toy though:

Having said all that the current state of the game is still toy-like. There isn't a lot of gameplay after the initial solving of factory automation. To turn Byproduct into a proper game there needs to be features that take full advantage of the chemistry system. I have a variety of plans going forward. But this post has already gone on long enough. I plan to write another post either later this week or a little beyond that.

If you've read this far, thank you so much for your time. I'd love to hear your opinions. Do you think this was a little over the top? Or an interesting diversion into procedural content? If your a programmer how would you have solved this problem?

Thanks for reading.

The Almechanist

Get Byproduct

Byproduct

Factory game with no conveyors, oh no! Loop recipies to move items.

| Status | In development |

| Author | The Almechanist |

| Genre | Puzzle, Simulation |

| Tags | Abstract, Automation, Difficult, factory, Game Maker's Toolkit Jam, Godot, Indie, Minimalist, Singleplayer |

More posts

- Improve or Extend? Or both?18 days ago

- Suit up! New chemistry and QoL updates24 days ago

- Bug fix update46 days ago

- New Chemistry and many many bugs...48 days ago

- Progress Update No265 days ago

- Turning A New Page92 days ago

- Progress Update99 days ago

- Byproducts New Lick Of Paint!Aug 20, 2025

- Small updateAug 17, 2025

Leave a comment

Log in with itch.io to leave a comment.